Richard Strauss 1945.

The story of a never shown film role Richard Strauss shows in his garden. The visits of Klaus Mann and William Wyler to Garmisch in 1945. The great old master of European classicism and his behaviour in the Nazi empire.

For some years I have been looking for film material about German history in the National Archives in College Park. I noticed some material that I didn’t know much about at first. But as always, stories that can be material for an exciting reportage are tied to such shots.

William Wyler in as a war reporter Germany

The composer Richard Strauss was filmed in his garden in Garmisch at the beginning of June 1945. Back then, in the early summer of 1945, film director William Wyler came to southern Germany with a US Air Force film team. Wyler shot color films for the film Thunderbolt!” in Munich, Berchtesgaden, Dachau and other places. The film was taken during a visit to Richard Strauss in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

A very unusual theme, at least in the context of these Wyler films. This footage was never published because Wyler only finished the first of his two planned films because of the end of the war. In the other preserved film roles, which I reviewed and scanned together with Elisabeth Hartjens in the American National Archives, Wyler’s cameramen mainly film the effects of the bombardments of German cities. So why Richard Strauss?

William Wyler and Richard Strauss

We see Strauss with peonies in the garden of the Strauss Villa at Zoeppritzstraße 42 in Garmisch. Little is known about the meeting of Wyler and Strauss. Strauss reads in the score of the opera “Die Liebe der Danae”, which was written between 1938 and 1940 and was first performed in Salzburg in a public dress rehearsal in the summer of 1944. The world premiere of the opera did not take place until 1952 in Salzburg. What is unusual about the style of the recordings are the numerous close ups by Richard Strauss. There are no portraits of any other personality in the collection of these Wyler films.

The US Army and the Strauss Villa

Garmisch-Partenkirchen had been conquered by the US Army on April 30, 1945. On the day of Hitler’s suicide. A troop of the US Army invaded the Strauss Villa to make quarters in the magnificent house. So the 80-year-old composer faced – in Garmisch snow fell that day – the wet and exhausted GIs. He describes in his memoirs that he had introduced himself as the composer of the Rosenkavalier, whereupon the Americans immediately left. Some of the American soldiers involved, however, describe the encounter somewhat differently. The Strauss family served food to the GIs and Richard Strauss played the piano in the living room. This was not very helpful, the Strauss family actually had to leave the house for a few hours. But the soldiers were instructed to move on immediately towards Innsbruck, so they left the house again. Why the Americans had to continue so suddenly has to do with another exciting story – the fights in the Inn valley for Castle Iter. Anyway, the Strauss family can go back to their house.

Lieutenant Alfred Mann

On the evening of the same 30 April, the musicologist and American lieutenant Alfred Mann also came to the Villa von Strauss – Richard Strauss is well known to him. Alfred Mann is the son of the pianist Edith Weiss-Mann. An emigrated connoisseur of Germany and an admirer of Strauss with influence high up. “When the tall, imposing figure of the eighty-year old man appeared in the door frame, it seemed to me as if a chapter from music history were opening before my eyes”. In any case, the Strauss Villa becomes “off limit” after the arrival of Alfred Mann – the US Army now holds its hand over the house of the famous composer and in May 1945 Richard Strauss is the subject of lively visitor tourism. Alfred Mann has nothing to do with another gentleman who will visit Strauss. This Mann is no less a man than Thomas Mann’s son.

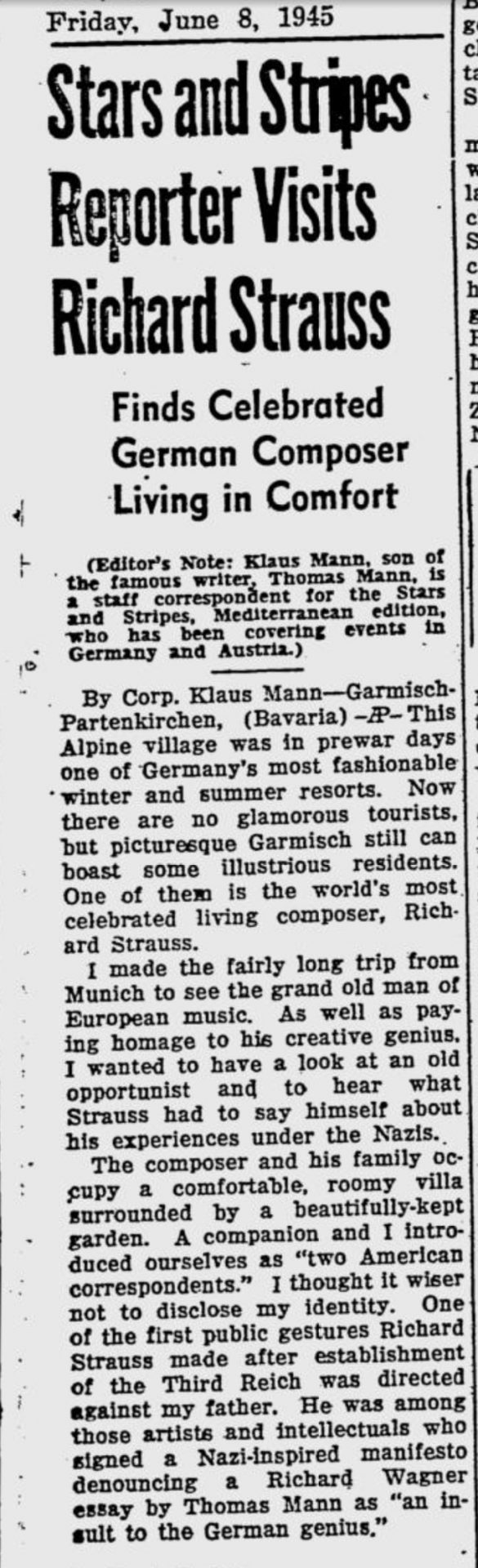

War Correspondent Klaus Mann

Klaus Mann meets Richard Strauss on 15 May, a wonderful summer day, as he writes. Are the recordings from this context? “I thought it wiser not to disclose my identity,” notes Klaus Mann. The day before, he had visited his destroyed parental home in Poschinger Strasse in Munich. The loss of status and existence was painfully experienced. Now, incognito, he visited the stately villa of an artist who had stayed in Nazi Germany.

By Cpl. KLAUS MANN Staff Correspondent GARMISCH-PARTENKIRCHEN (Bavaria). May 26, (Delayed) – This Alpine village is one of Germany’s most fashionable winter and summer resorts. Now there are no glamorous tourists, but picturesque Garmisch can still boast some illustrious residents. One of them is the world’s most celebrated living composer, Strauss. I made the fairly long trip from Munich to the grand old man of European music. As well as paying homage to his creative genius, I wanted to have a look at an old opportunist about whose behavior during the past 12 years there have been rather unsavory stories. It would be interesting, I thougth, to hear what Strauss had to experience under the Nazi regime. The composer and his occupy a comfortable, roomy villa surrounded by a large, beautifully-kept garden. A companion and I as “two American correspondents” I thought it was not to disclose my identity…”

(…) … “he was all smiles and gracious cordiality as he shook hands health was just fine, he assured us- and, in fact, he looked surprisingly well preserved of 83. His face, with its pinkish complexion, beamed serenely under his silver hair. There was nothing senile about him. NO MORE PLANS Yet when we asked him about his artistic plans he shook his head with philosophical resignation: “No plans for me anymore! I ‘ve written 15 operas, not to mention my symphonic pieces and my many songs. That’s enough for one lifetime. Don’t you think I have deserved some rest?” We agreed, then listened respectfully to his complaints about the way in which the defunct Nazi regime had been dealing with his recent opera “Die Liebe der Danae” (Danae’s Love). The master resented such lack of consideration on the part of a government with whom he had otherwise been on correct, if not friendly, terms. “Of course”, he said, “this was not the first disturbing incident. I have had two rather serious conflicts with the Nazi administration.”

Three German Masters

In “Three German Masters” (Strauss, Emil Jannings, Franz Lehar), Klaus Mann attempts to trace the opportunism of those artists who pacted with Hitler. Although they could have easily turned their backs on the regime because of their international fame. The conversation between Klaus Mann and Richard Strauss actually revolves around the “Love of Danae”, which should have been premiered in Salzburg on August 5, 1944 – but the performance was cancelled because of the assassination attempt by Count Stauffenberg. Strauss interprets the dismissal of his play as a “conflict” with the regime – as Klaus Mann ironically notes with quotation marks. At that time the Salzburg Festival had indeed been cancelled – not a single piece by Richard Strauss.

Wylers footage

Wyler’s film camera doesn’t accidentally go into exactly this piece “The Love of Danae”. The scenes of the raw material are staged throughout, from the peonies (shot twice in the raw material) to the close ups of the quietly singing composer reading the score. Klaus Mann describes his conversation “in front of his stately villa, under the beautiful trees of his large well-kept garden”. And mentions that he had two companions. This is exactly where the camera targets Richard Strauss and does not fail to find a symbol for the magnificent garden beforehand.

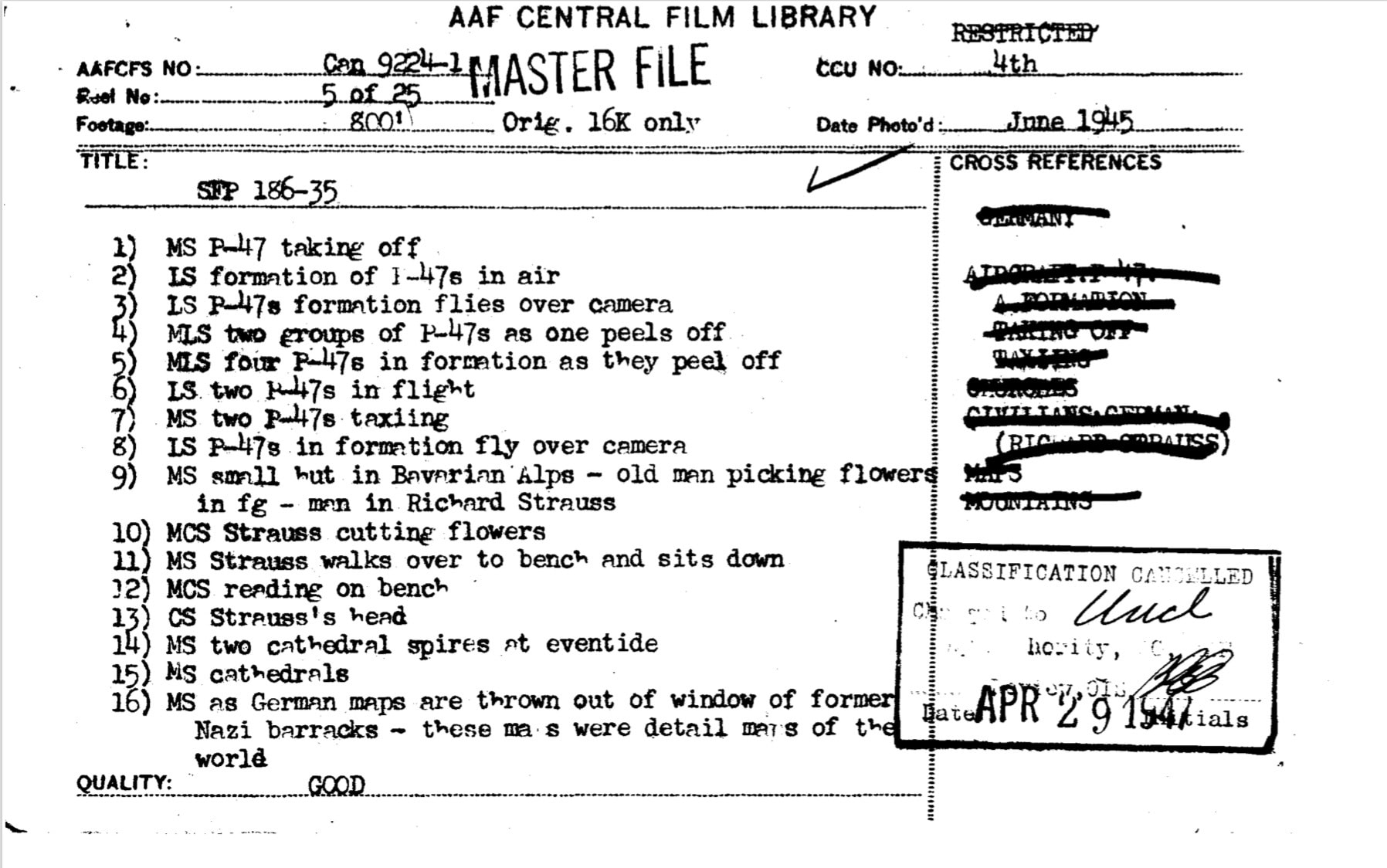

What is noted in the National Archives

However, the index card for the film material shown here notes that the “Can 9224-1” was shot in June 1945: “Medium shot small hut in the Bavarian Alps – old man picking flowers in foreground – man in Richard Strauss” and “Date Photo’d: June 1945”. The film material was recorded in June 1945 for further processing in New York. During Klaus Mann’s visit, the footage was certainly not shot. But William Wyler knows Klaus Mann from Hollywood. Mann’s report on his encounter with Richard Strauss appears on 29 May 1945 in the American soldier newspaper “The stars and Stripes” under the title “Strauss still unabashed about ties with the nazis”. One day after the article by Klaus Mann, Wyler sends one of his teams to Garmisch and they shoot the footage with Richard Strauss. As Wyler had already made his way back to the U.S. that time, it is unlikely that he met Richard Strauss in person. What is really going on behind the forehead of this world-famous composer? “The love of Danae” – a piece of cheerful renunciation? The naive egocentric? The opportunist?

To be continued

Stephan Bleek

Leave A Comment